Online Viewing Room

Punu Mukuyi mask

Gabon

Carved wood and pigments

Early 20th century

Height: 13 ¾ in. (35 cm)

Provenance:

Collected before 1908 by Edouard Emile Léon Telle (born 1859), Governor of Gabon (1907-1908)

By descent until 2017

Publication / Exhibition:

“Gabon”, Galerie Philippe Ratton, June-Sept. 2017 p. 73

African Heritage Documentation & Research Centre Archive #ao-0138145

Sold

This ritual “M’Pongwe Mukuyi” (also called “mukudj” or “okuyi”) mask is the representation of an idealized woman’s face. It superbly combines expressivity and grace.

As stated by A. LaGamma (1995), these masks were used during the mwiri ceremonies, an important male initiation society spread throughout southern and central Gabon. They appeared during community rituals linked to important events of village life (funerals, end of mourning, youth initiation, transgressions of clan orders, birth, epidemics, etc).

Representing female entities from the world of spirits or the dead, the masks capture an ideal of beauty.

Senufo figure

Ivory Coast (Côte d’Ivoire)

Carved wood

Early 20th century

Height: 22 ¼ in. (56.5 cm)

Provenance:

Ex Sotheby’s, January 8th, 1968, lot 12

Ex collection Hans Schleger (1898-1976), London, UK

Ex collection Adrian Schlag, Brussels, Belgium, 2007

Publication & Exhibition:

“Archetypes”, Tribal Art Classics, TEFAF 2017, pp. 24-27

African Heritage Documentation & Research Centre Archive: 0140144

Sold

The Senufo people are farmers, living in a savanna zone covering the north of Ivory Coast, the south of Mali and the southwest of Burkina Faso. The first mention of them was in 1888 by Louis Gustave Binger, a naval infantry officer.

Senufo statuary is distinguished by its aesthetic refinement, where pure lines combine a hieratic quality and movement. Senufo female figures were notably used by members of the Sando (Sando’o) secret society for soothsaying purposes. Female figures represent celebrations of fertility.

The figure shown here is distinguished by its geometric construction and delicate features.

The tension of the face projecting forward is counterbalanced by the pronounced curve of the back and the slenderness of the neck, underlining the superb upright posture of the figure. Another interesting feature is the masked-shaped receptacle carved on the top of the head.

Heddle pulley

Baule, Ivory Coast

Carved wood

Early 20th century

Height: 7 ¼ in. (18.5 cm)

Provenance:

Ex collection Alain Lecomte, Paris

Ex private collection, France

Sold

This is a superb example of anthropomorphic heddle pulley by the Baule people of Côte d’Ivoire. This sculpture is distinguished by the delicacy of the carving and the refined rendering of the face features and coiffure. The face conveys an intense sense of serenity and sacredness. The fine-aged, deep brown patina and signs of wear attest to the prolonged use of this heddle pulley.

The most common weaving technique in West Africa is to use cotton strips about 15 centimeters wide and sew them together to make clothes. Weaving is a male job, while cotton spinning is done by women.

As stated by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used on the traditional narrow-band loom, heddle pulleys are functional objects used to ease the movements of the heddles while separating the warp threads and allowing the shuttle to seamlessly pass through the layers of thread. Scholars have suggested that the prominent display of pulleys, hanging over the weaver’s loom in the public place, afforded artists their best opportunity to showcase their carving skills, in the hope to attract commissions for figures and masks.

Commemorative portrait of a chief Singiti figure

Hemba

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Carved wood

Early 20th century

Height: 27 ¼ in. (69 cm)

Provenance:

Ex collection Hendrik Elias (1925-2014)

Ex Galerie Elmar, Wieze, Belgium, circa 1975

Ex collection Jacky de Maeyer, Antwerp, Belgium

Ex collection Adrian Schlag, Brussels, Belgium

Publication:

“Hendrik Elias’ Legacy Archives”, 2018, J. de Buck, page 12 & fig. 7 page 30

African Heritage Documentation & Research Centre Archive: 0153329

110,000 Euros

As stated by François Neyt in the reference book La grande statuaire Hemba du Zaïre (1977), Hemba ancestor effigies were carved to honor the legacy of important chiefs (singiti). The concept of lineage protection and survival played a central role in Hemba beliefs. “The Hemba clans, relatively independent of each other, had their own history. Their family trees dating back to eight, ten, or even fifteen generations were perfectly known, and were essential in particular to justify ownership of the land.” (Neyt, p. 25)

These commemorative portraits of chiefs were genealogy markers. They also served as protectors of the clan.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York notes that Hemba artists emphasized two bodily passages of such representations – the head as the site of one’s intellect where knowledge is taken in through the eyes and the stomach where the umbilicus is the point of connection with one’s extended lineage. A Hemba chief inherited a series of such works that were housed in a dedicated structure centrally located in the community adjacent to his residence.

This ancestor figure originates from the northern Hemba region, close to the Kusu and Bassikasingo. The Cubist stylization of the features is a notable Bassikasingo influence.

The composition of the figure combines power and harmony. The coiffure with four braids is a distinctive feature of sculptures from a limited corpus collected in the Luama river area. The best known examples are the Hemba-Kusu figure from the Musée du Quai Branly, formerly in the collection of Jacques Kerchache or the naturalistic figure acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2015.

Large Hei Tiki pendant

Maori

New Zealand

Carved greenstone (Pounamu – nephrite) and abalone (paua shell)

19th century or earlier

Height: 5 ½ in. (14 cm)

Provenance:

Ex collection Serge Brignoni (1903-2002), Switzerland

Ex collection Edmund Muller (1898-1976), Beromünster, Switzerland, acquired in 1956

(inv. n° 3720c)

Ex Sotheby’s New York, 22 November 1998, “Property from the Foundation Dr. Edmund Müller”, lot 6

Ex collection Leo & Lillian Fortess, Honolulu, USA, acquired from the above auction

(inv. n° 161G)

Ex collection Eric & Esther Fortess, Boston, USA

Ex collection Alex Philips, Melbourne, Australia

Sold

This carved figure is a representation of the Maori people’s original ancestor. This Hei Tiki pendant was carved in a superb piece of nephrite (pounamu in the Maori language). This greenstone, which is found only on the South Island of New Zealand, was a highly valuable material and particularly prized by the Maori for its hardness and its color.

The figure is shown head-on, its head leaning to the left, and sticking its tongue out – the symbol of the power of the warrior in Maori art. The facial features (bridge of the nose, mouth, eyes) are delicate, carved deeply into the stone.

Hei Tiki pendants were worn around the neck on a narrow cord of woven fibers. These ornaments were prestigious, and were passed on from generation to generation. Hei Tiki were said to confer the protection of the ancestors of the clan to the wearer, with the clan’s affiliation going back to Tiki, the primordial man.

Lor mask

Duke of York Islands, north of the Gazelle Peninsula, New Britain

Bismarck Archipelago

Carved wood, pigments, vegetal fiber

Early 20th century

Height: 12 ½ in. (31.5 cm)

Provenance:

Ex private estate, Adelaide, Australia

Ex collection Joost & Truus Daalder, Australia acquired in the 1990s

16,000 Euros

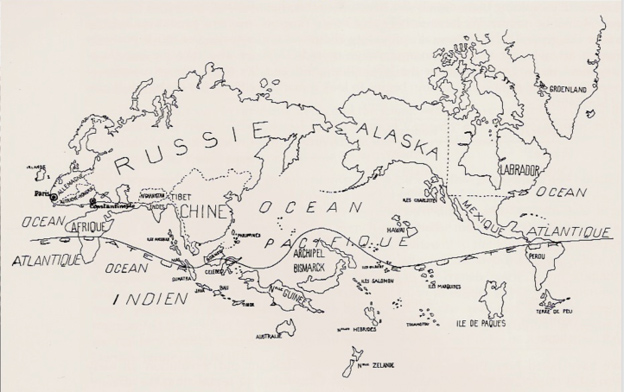

The art of New Ireland and New Britain in Melanesia, Oceania has fascinated Western artists since the beginning of the 20th century and most notably the Surrealists. In the celebrated 1929 map attributed to Paul Eluard, the Surrealists placed the Bismarck archipelago at the center of the world.

As Philippe Peltier notes in Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie – Fleurons du musée Barbier-Mueller, 2007 p. 314, the Duke of York Islands are located a few nautical miles off the coast between the Gazelle Peninsula and southern New Ireland. In 1900, a colonial census listed only 3,373 inhabitants left on the islands. Little ethnographic data on ancient societies was ever recorded. The main source of information is Richard Parkinson’s “Thirty years in the South Seas” published in 1907.

The population originally came from southern New Ireland and still shared many cultural traits with this region. In addition to the dukduk societies, Parkinson mentions wooden masks with a large, menacing smile. He refers to these masks as lor (or lorr).

In the idioms of this region, lor refers at once to the skull and the masks, as well as to the rituals where they appeared. Lor masks are related to spirits and death.

The significance of lor masks in the Duke of York Islands is uncertain, but they likely played similar roles to those of Tolai, where the tradition persists. Today, Tolai lor masks are worn by performers in a dance called tambaran kakao (spirit that crawls). The masks reportedly represent a spirit that comes to a local leader in dreams and reveals the details of dance paraphernalia and choreography.

In earlier times, during funeral ceremonies, Lor masked dancers appeared on the occasion of the redistribution of wealth. This task was deemed too delicate to be undertaken by unmasked men. At other times, they danced before the arrival of dukduk masks or during female initiation ceremonies.

Surrealist world map

Surrealist world map

Yipwon hook figure

Middle Sepik, Korewori River

Papua New Guinea

Carved wood and shell

First part of the 20th century

Height: 18 ¾ in. (48 cm)

Provenance:

Ex collection Naomi Lindstrom (1924-2014), USA

Ex collection Todd Barlin, Sydney

18,000 Euros

Flowing through the neighboring chains of hills and swamplands, the Korewori River (formerly the Karawari) is one of the numerous tributaries of the Sepik, the river that sustains the populations of the eastern part of the island of Papua New Guinea.

The discovery of Korewori art (Middle Sepik) constituted a major intellectual and artistic shock for the West.

The ritual figures called yipwon were linked to hunting and warfare. According to one of the founding myths of the Korewori, the yipwon were children of the Sun, conceived from wood shavings that fell during the carving of the first drum. One day, prompted by his warrior instinct, one of the yipwon children committed a murder. Out of fear of reprisal, he took refuge in the Men’s House and turned into a wooden statue. Outraged by the behavior of his offspring, the Sun left the Earth, leaving the yipwon there, their mission henceforth being to serve as guides for men, in particular on head-hunting expeditions against neighboring enemies.

Large-scale yipwon belonged to the whole clan; they were kept in the Men’s House or in sacred caves reserved for religious ceremonies. Small-scale charms were personal and used by individual warriors.

Before going to battle, the yipwon were invoked to insure the success of the war party, becoming responsible for extinguishing the vital energy and fighting spirit of their enemies, thus making them vulnerable during battle. In case of victory, yipwon were celebrated during ceremonies, receiving offerings of libations. In case of defeat, however, they were abandoned.

Yipwon sculptures feature both the interior and the exterior of the body, skeleton as well as internal organs, and facial features. The rounded parts in the middle of the hooks symbolize the vital core that fires up the warrior spirit.

These anthropomorphic spirit figures feature silhouettes punctuated with curves and sharply pointed elements interacting with empty and full volumes.

In 1960, the Museum of Primitive Art in New York showed Korewori hook figures for the first time, but it was not until 1968 that a groundbreaking exhibition dedicated to the art of this region, “Caves of Karawari” was organized at D’Arcy Galleries in New York.

This exhibition allowed the public to discover an aesthetic combining boldness of form, modernity, and ferocity.

The resonance of the ancient art of the Korewori with the work of artists like Henry Moore, Roberto Matta and Alberto Giacometti is fascinating.

In the late 1930s, the British sculptor Henry Moore (1898–1986) seemed irresistibly attracted by sharply pointed, hooked shapes, as illustrated by his preparatory drawings from the period.

In the reference book, “Primitivism in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern” (MoMA New York, 1984, p. 607), Alan Wilkinson noted the marked interest of the artist for Oceanic sculpture. In a text from 1941, Henry Moore himself evoked “New Guinea carvings, with drawn out spider-like extensions and bird-beak elongations…“.

Henry Moore Three Points, 1939-1940

Henry Moore Three Points, 1939-1940

The Tate Modern, Londres (inv. T02269)

Alberto Giacometti Homme et Femme (Le couple), 1928

Musée d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris (inv. AM 1984-355)

Provenance

This Yipwon hook figure is distinguished by its warlike elegance and dynamism.

It comes from the collection of Naomi Lindstrom (1924-2014), a passionate traveler who during her career at Pan Am crisscrossed the globe and assembled a remarkable collection of art from around the world.

It was later acquired by prominent Oceanic Art dealer Todd Barlin from Sydney.

Museum references

Chilean surrealist artist Roberto Matta owned several hook sculptures, including the famous large yipwon figure now in the collection of the De Young Museum of Fine Arts in San Francisco ( inv.2000.172 .1 )

Bibliographic references

– Caves of Karawari, introduction by Dr. Eike Haberland, photographs by Bill Viola, published by D’Arcy Galleries, 1968, NY, NY, USA.

– Oceanic and Indonesian Art, edited by Harry Beran, The Oceanic Art Society, PO Box 678, Woollahra, NSW, Australia 2025, 1998, p. 8

– Die Yimar am oberen Korowori. Studien zur Kulturkunde, E. Haberland, S. Seyfarth, Wiesbaden, Steiner Verlag, 1974

– Island Ancestors, the Masco collection, Allen Wardwell, The Detroit Institute of Arts Founders Society

– Art Papou : Austronésiens et papous de Nouvelle Guinée Alain Nicolas, Musées de Marseille, RMN, 2000

– New Guinea Art Masterpieces from the Jolika Collection Marcia and John Friede, De Young Museum, San Francisco, 2006

– Arts des mers du Sud Collections du Musée Barbier Mueller

sous la direction de Douglas Newton Marseille, 1998

– Arts of South Seas, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1946

– Ombres de Nouvelle Guinée, Philippe Peltier et Dirk Smidt, Somogy Barbier Mueller, Paris, 2006

– L’art Océanien, Adrienne L. Kaeppler, Christian Kaufman, Douglas Newton, 1993, Editions Citadelles & Mazenod

– Kunst Vom Sepik, Heinz Kelm, Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin, 1966

– Sepik, musée du quai Branly – Skira Paris, 2015

– Sepik, Crochets, Figures et Masques, Galerie Flak, Paris 2018

Ancestor figure

Coastal area or Nagum Boiken

Papua New Guinea

Northern Sepik

Carved wood, fiber, pigments

Late 19th or early 20th century

Height: 9 ¾ in. (25 cm)

Provenance:

Ex collection Charles Ratton, Paris

Ex Loudmer, Arts Primitifs, June 27th, 1991

Ex collection Georges Goldfayn, Paris since 1991

32,000 Euros

The strikingly dynamic figure presented here is emblematic of the cultures of the Sepik coastal area, and presumably originates from the Nagum Boiken peoples.

This incarnation of such mythological clan spirit played a prominent role in the initiations of young men. It also served during other events marking different stages in their lives (war, rituals, social events, etc.).

Guardians of the clan’s well-being, these figures were kept in the Men’s House. A place for sharing and discussion, the Men’s House constituted the very heart of the ceremonial life in the villages of the Sepik.

In terms of provenance, this figure formerly belonged to legendary antiques dealer Charles Ratton in Paris.

It was acquired at a Paris auction in 1991 by George Goldfayn (1933-2019), an author, publisher, man of letters and cinema. Passionate about art, he was closely associated with the Surrealist circle in Paris from 1950 onwards. A close friend and confidant of André Breton, Georges Goldfayn participated in the launch of the gallery À l’Étoile scellée, 11 rue du Pré-aux-Clercs in Paris at the end of 1952. Breton was the artistic director while Goldfayn was the gallery administrator.

Under the aegis of André Breton, he began collecting ancient Oceanic and North American art in the 1950s and continued to do so until his death.

Hemis Katsina – New corn kachina doll

Hopi, Arizona, USA

Carved wood (cottonwood) and natural pigments

Circa 1900-1910

Height: 14 ¼ in. (36.5 cm)

Provenance:

Ex collection George E. Shaw, Colorado

Sold

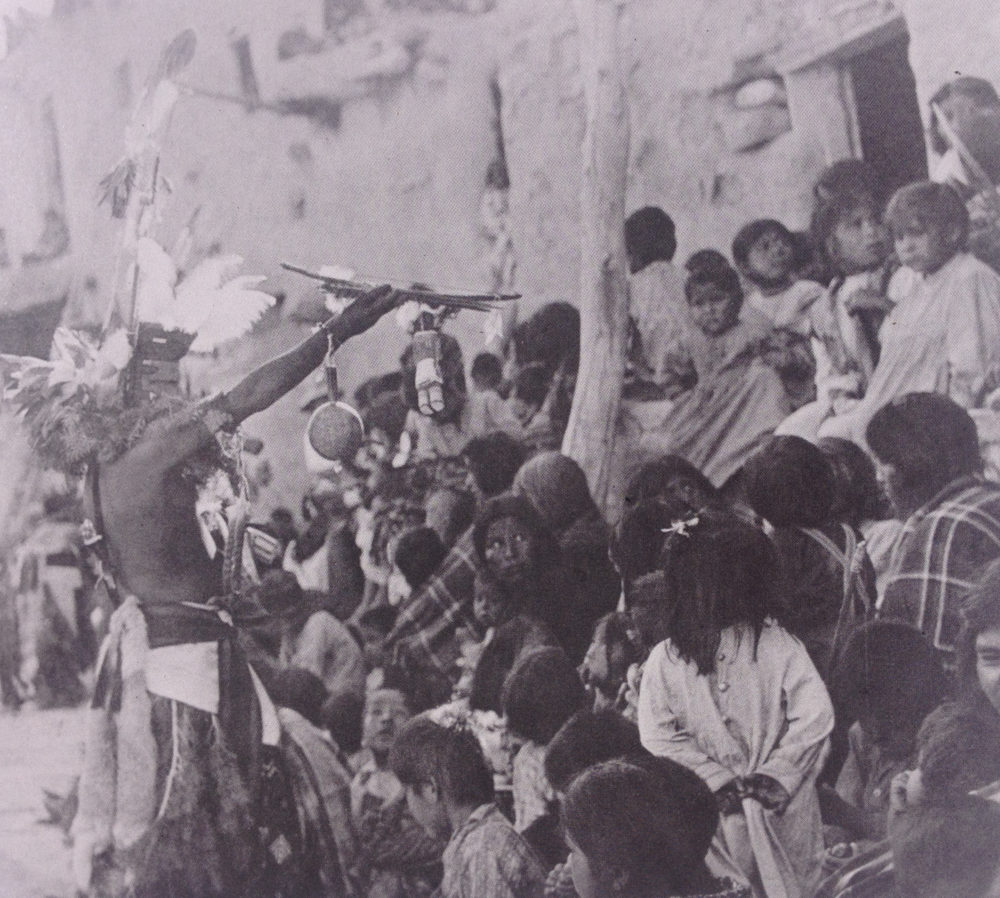

Kachina dolls (or katsinam) represent spirits or gods from the pantheon of the Pueblo peoples in the American Southwest. Given to children, kachina dolls constituted a pedagogical tool allowing them to familiarize themselves with the spiritual world and perpetuating knowledge of the founding myths on which their society was based.

Hemis Kachina appears notably during the Niman or Home-Going Ceremony when the kachinas leave the Mesas for six months. It is one of the most appropriate kachinas for this farewell, as it is the first kachina to bring mature corn to the people, indicating that the corn crop is assured.

Tawa Koyung Katsina – Peacock Kachina doll (variant)

Hopi, Arizona, USA

Carved wood (cottonwood), natural pigments and feathers

Circa 1900-1910

Height: 10 ½ in (27 cm)

Provenance:

Presumably The Heye Foundation, Museum of the American Indian, New York Inv# 19/4088

Ex collection John Molloy, New York

Ex collection Galerie Flak, Paris

Ex private collection, France

Sold

Tawa Koyung (Peacock) is an exceedingly rare kachina. Peacock Kachina dancers can be seen during the Soyohim Mixed Dance. This kachina sprit is thought to be borrowed from Rio Grande region. There is some similarity to Muzribi kachina (Bean Kachina).

Hon Katsina – Bear Kachina doll

Hopi, Arizona, USA

Carved wood (cottonwood), natural pigments and feathers

Circa 1910

Height: 11 in. (28 cm)

Sold

The Bear Clan is one of the oldest clans among the Hopi. One of its distinctive symbols is the bear paw print which was notably found on ancient petroglyphs displaying the history of the Hopi tribe (Tutuveni & Dawa Park in Arizona). This symbol is visible of the cheeks of this kachina doll.

Hon, the Bear Kachina, yields great power. He is capable of curing the sick. Bears are considered to be great warriors.

Hemis Katsina – New corn kachina doll

Hopi, Arizona, USA

Carved wood (cottonwood) and natural pigments

Circa 1900

Height: 15 ¼ in. (39 cm)

Provenance:

Ex collection George E. Shaw, Colorado

Ex collection James & Marilynn Alsdorf, Chicago,

acquired from above on July 22th, 1985

Sold

“Kachina”: one word says it all! For the Hopi people of Arizona in the American Southwest, “Kachina” (plural “Katsinam”) means wooden statuette, masked dancer or deity. Kachina dolls were given to children, and constituted a teaching tool allowing them to familiarize themselves with the spiritual world and perpetuating knowledge of the founding myths on which their society was based.

Objects of tradition and of education, tools to remember and works of art in their own right, kachina dolls give vibrant testimony to the traditions and secret beliefs of Native Americans of the Southwest.

Carved head

Old Bering Sea II Culture

(Archaic Eskimo)

Alaska

100 – 500 A.D.

Carved walrus tooth

Height: 2 ¾ in. (7.6 cm)

Provenance:

Collected on St Lawrence Island early 1990s

Ex collection Jeffrey Myers, USA

Ex collection Perry J. Lewis, USA

Ex private collection, USA

Published & exhibited:

Espiritus del agua, Barcelona & Madrid, Spain, 1999-2000

Art of the Ancestors, Aspen Museum of Art, Colorado, 2004

Sold

This head, sculpted in a partially fossilized walrus tusk is quite exceptional in terms of its spare lines, its refinement and in the extreme stylization of the features. The way in which the features are stretched across the face confers a remarkable elegance and interiority to the sculpture, reminiscent of the art of Giacometti or of Brancusi.

The style is characteristic of the Old Bering Sea II culture, an archaic civilization of the Arctic which developed on St. Lawrence Island in the southern Bering Strait in Alaska during the first millennium B.C.

A veritable giant in miniature, this head has a timeless, universal quality to it.

Discover the virtual tour of our Parcours des Mondes exhibition